Nostalgia with Margaret Watson: Thousands of Dewsbury people moved home in slum clearance programme in the 1950s and 60s

Margaret Watson writes: Also, how young couples cannot afford the deposit needed to get a mortgage because the price of houses is soaring.

But there was a different kind of housing crisis when I was a girl and the council solved it by building thousands of council houses for those who couldn’t afford to buy their own.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThousands of people were moved from one end of Dewsbury to the other as part of the town’s ambitious slum clearance programme.

The houses people were living in at the time were mainly back-to-back and had been built at the height of the Industrial Revolution for families flocking to Dewsbury seeking work.

Overcrowding was rife and it was quite common to find families with eight or nine children, sometimes more, living in two rooms – one up and one down.

Some families were living in one-roomed dwellings, usually referred to as cellar kitchens, and in 1923 there were 393 such dwellings in Dewsbury containing a total of 850 people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd 10 years later, the number had increased to 441with 993 living in them and paying rents ranging from two shillings to six shillings a week.

One of the most densely populated areas was Westtown where the Irish community had settled, and some houses were in such a dilapidated condition landlords offered them free to the council to do with what they wanted

In the early 1900s, the owner of a row of such houses in Asylum Road, near St Paulinus Church, gave the houses to the council because he could not afford to repair them to the standard they were demanding.

Some unscrupulous property owners took rents but never carried out repairs, and if the tenant fell into arrears, the bailiffs were called in and the family evicted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut not all landlords were like this, for there were those who built decent houses and maintained them well, and I know of some which are still standing.

The best houses were those owned by the Co-op, but the demand for these was so great there were often as many as a thousand people on the waiting list.

The council started to build its own houses in the 1900s, but it was only building 150 a year, nothing like the vast number needed.

Most of them were built on the fringes of the borough, like the Pilgrim Farm estate, Dewsbury Moor and Beckett Nook.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose lucky enough to get one had to be vetted and be able to afford the rent because there were no housing benefits in those days.

One man who more than any other fought for decent housing for the poor was Tom Myers, of Thornhill Lees, who served on the council, was Mayor of the Borough, and later became Labour MP for the Spen Valley.

He was a thorn in the side of the council, condemning it repeatedly in the council chamber and in the Reporter for its poor housing policies.

Councillor Myers blamed the town’s high rate of infant mortality, the highest in Yorkshire, and diseases such as TB and diphtheria, on poor housing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1933 he wrote to the Reporter accusing some councillors of not dealing with the matter and said some of the houses concerned were owned by members of the council.

There were 7,000 back-to-back houses in Dewsbury at that time and Councillor Myers said they had to be dealt with if Dewsbury was going to reduce its shocking infant mortality rate.

He reminded them that 30 years previously the Lancet referred to the slums in Eastborough, Flatts and Springfield, but they were still here and were in much the same condition as they were then.

He said every house had been paid for three times over in the rent demanded since the Lancet declaration was made.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said over half of the population of Dewsbury was paying high prices for an inferior article in the form of low grade housing accommodation.

The council’s five-year plan to build 150 houses a year could not possibly ease the situation, the minimum should be 2,000.

But it was to be many years before Dewsbury launched a massive house building programme that was to be the envy of most councils in the country.

Even after World War two, the housing situation in Dewsbury was desperate and some families had to resort to living in wooden huts on Caulms Wood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe huts had been home to the soldiers who had manned the guns up there, but when they vacated them at the end of the war, squatters moved in and

took over.

Within hours of the soldiers leaving, families from all over the area descended on the camp, breaking the padlock on the iron gates to get in.

Nobody had foreseen this, and it took the council, who had ownership of the huts, sometime before they could sort out the situation.

Some families were eventually evicted; especially those who had come over from Ossett, but others were allowed to stay, much to the dismay of some local residents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, a settled community was quickly established there, much to the dismay of people living nearby, who complained that the camp was spoiling the area.

One local councillor visiting the site disagreed and said some of those living in the huts had converted them into “little palaces” and he begged people not to tar everyone one with the same brush.

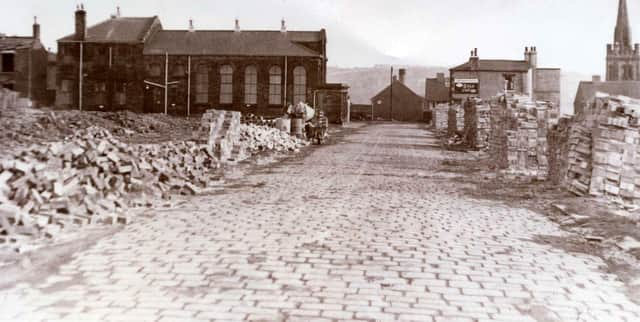

The picture above taken in Thornton Street, Westtown, shows what happened to communities when the bulldozers arrived during the slum clearances of the 1950s and 60s.

Whole streets disappeared to be replaced by houses and flats, and so did churches and pubs.

Luckily the church on the left still remains – Providence Independent Methodist Church – but sadly the one on the right – St John the Baptist was demolished.