Ramadhan In 1960's Dewsbury through the eyes of Mohammad Afzal

and live on Freeview channel 276

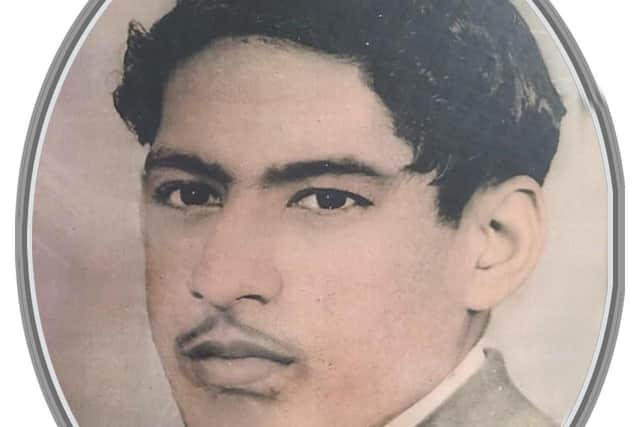

Mr. Haji Mohammad Afzal of Gardens Crescent Street in Ravensthorpe was one of the men who came to Dewsbury in September 1960 at the age of 24 as a second-generation migrant from Pakistan.

He was part of a large group of Indian and Pakistani nationals who were encouraged to come and work in our local mills throughout the post-war decades of the 1960's and 1970's.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese men came to Britain because of a severe labour shortage existing during that period across the whole country.

As someone who now belongs to a dwindling generation, “Haji Afzal” agreed to talk in this feature about what the area's Pakistani residents like him did in that actual Sixties decade when the month of Ramadhan was announced over the radio.

Speaking to the Reporter Series, Mr. Afzal said: "Dewsbury was a very different place when I first came from Pakistan during September 1960 to work in the town's mills."

"Like a lot of other Indian and Pakistani migrant workers, I had to swiftly adapt and get used to a whole new different culture.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Ramadhan In 1960’s Dewsbury was also a big contrast in culture compared to these days.

"A new Moon always signals the start of the four weeks of Ramadhan fasting. But It was impossible to see anything over Dewsbury's skyline in those days because of all the smoke and fumes coming out of the tall mill chimneys. A large number of these mills eventually closed and have now been demolished.

"The weather was also very different with ongoing rainfall, regular mist and heavy fog. We hardly ever saw any sunlight. So, to see a new Moon was out of the question!

"Today, our families can receive up to date reliable information on sightings of the new Ramadhan Moon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"This is an age when we have got used to having annual Ramadhan prayer timetables printed by every Mosque. The time-charts are given out free to the congregations a few days before the holy month of fasting is about to start. Worshippers can take them off their local Mosque's reception table.

"Thanks to these charts, each family has information over the next four weeks on the exact times for dawn (when the fasting begins) and for sunset (when the fasting is due to end in the evening). Everything is clearly written, along with 'Namaz' prayer hours on the Ramadhan timetable.

"The younger generation can in some neighbourhoods even download an exact electronic copy of their local Mosque's timetable onto the mobile phone's WhatsApp.

"All the information is given by the observatory in Greenwich.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"But my own generation never enjoyed such luxuries. The 1960’s was certainly not the digital era. We had no Sky television, no mobile phones, no internet, no Ramadhan timetables - and not even any mosques to guide us. Most of our houses did not even have a landline telephone in those days!

"There was however a possible solution to our Moon sighting dilemma.

"One common electrical marvel available to buy in our town's shops especially from the mid-1960's onwards - was the audio tape-recorder – with a radio fixed in it. We could listen to traditional South-Asian music as well as hear devotional Islamic Qawalis through these gadgets.

“My friends and I also found it easy to ‘tune into’ an Urdu radio station set up in Bradford to hear contemporary news on what was happening back ‘home’ in the Sub-Continent. At times, the frequency even 'picked up' Arabic-speaking radio stations based in Morocco!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The radio also proved to be a very handy tool for me to find out if the new ‘Ramadhan Moon’ had been sighted – or not?

"I began my fasting as soon news of the Moon sighting came through. Everything for me seemed to automatically fall into place from then onwards.

“A big hearted Indian Gujerati shopkeeper called 'Haji Ibrahim' became well known for regularly driving his van into Hanover Square in Westtown - where I lived for the first four years of my new Dewsbury life before I moved to settle permanently in Ravensthorpe. I bought my Ramadhan food from him.

"His van was always stocked with bags of Chapatti flour, along with various fruits and vegetables, and of course with Halal meat. He even had small packets of delicious Arabic dates to sell in those Ramadhan months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This smiling friendly gentleman was a lifeline for nearly every Muslim household in our area during that post-war Sixties decade. He would later go on to open up the popular 'Lubna Cash & Carry' in Bradford.

“Many people amongst my generation still speak fondly of Haji Ibrahim. He gave a valuable service in those days with his deliveries.”

A customary tradition amongst most Muslim cultures during Ramadhan is to eat something at dawn - before starting the day's fasting. This dawn meal is known as 'Sehri'.

Mr. Afzal added: "There was unfortunately no Ramadhan timetable during that Sixties decade in my house giving information on the daily timings for Sehri. So, I was always awake in the early hours of the morning looking out of the bedroom window at the dark sky trying my best to spot a very thin layer of dawn light.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Visibility was very poor in those post-war years due to the damp weather and I had to use my own judgement to guess when to stop eating.

"The changing times are now clearly written on the Ramadhan timetable.

"My wife had not yet arrived to join me from Pakistan, so I would quickly warm up a plate of curry with two Chapatis, and have a cup of tea for my 'Sehri' meal.

"We did not have microwaves in those days, and. I had to get into the habit - on occasions - of eating cold food or having only a glass of water at such an early time in the morning – especially if I accidentally got late getting out of bed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I also had to perform a ritual ablution wash known as 'Wazhu' - immediately after eating the food. This wash was done with icy cold water coming out of a small kitchen tap before I began reading my early morning Fajar-Namaz prayers!

“The freezing cold water bit into the fingers of my shivering hands. There was not enough time to warm up the water. The early morning praying had to be done, and finished off, before sunrise!

"It's also important to remember my generation lived in small back-to-back terraced houses in that decade.

"These homes had no insulation, no boilers, no central heating, no gas fires, no UPVC double-glazed windows, and not even any instant running hot water – something that would be unthinkable today! We really felt the cold. But it is amazing what the human body can cope with if times are hard.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"A daily routine for me after finishing my early morning prayers was to walk to work for most of the year through heavy drizzles of rain and knee-deep snow.

“Yet the four weeks of Ramadan fasting did not affect my job at the carpet manufacturing mill where I worked as a machine operator for 45 years.

"I often used my Ramadhan ‘lunch break’ at the factory to quietly read my second Zuhr-Namaz' prayer of the day whilst everyone else was eating their dinner.

“The prayers were read on a sheet of folded cardboard which I kept next to the machine where I worked. The mill often received deliveries of cotton reels packed in large cardboard boxes. I had kept one of these cardboards for a useful purpose!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The owner of my workplace was a lovely humane individual called Mr. William Graham. This big-hearted mill owner showed a great deal of affection and respect whenever he saw me bowing and prostrating on the cardboard as part of my ‘Namaz’ worship.

“In fact, Mr. Graham appointed me a Foreman in the year 1964 because he felt so impressed by my devout humble character.

"I usually came home in the evening after finishing my 12 to 14-hour mill shift just in time to prepare for the breaking of the fast.

“This special meal time is called 'Iftari' when Muslims can resume eating again after going without food and water for nearly fourteen hours!.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“These days we can see the lounge table covered with lots of different mouth-watering Iftari dishes. Our families are often spoilt for choice as to what they select to eat as soon as the fast is broken at sunset.

"There are ‘starter’ trays of Samosas, Kebabs, and Onion Bhajis, along with mouth-watering Biryani dishes, a selection of curries, a huge variety of fruits - not to forget the delicious dates, and of course different types of tasty desserts to ‘top off’ the evening meal.

"We can now even buy big Ramadhan cakes at Muslim owned bakeries!

"The women in our neighbourhoods also share their cooking with each other. There is so much friendship and colour in our communities during this holy month! Looking back at my own austere life in the 1960’s, I tend to see all these things as a huge blessing from the Lord.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"But the 'Iftari' supper however for my generation living through those post-war years was very modest compared to these days. It was usually a sliced apple, perhaps some grapes if I was lucky, a few dates, a banana, a glass of water, and just one plate of curry with Chapatis.

"I had been a devout practising Muslim ever since my teenage years and my 'Imaan' – my faith - remained very firm even during that tough 1960’s era.

“The love which I had for my religion was far too strong to deter me from keeping those memorable post-war Ramadhan fasts.

"Ramadhan is also about testing yourself, and those years of fasting indeed tested our willpower.

“The fasting we are doing these days is very different and definitely much easier compared to the 1960's."